Something to Talk About in Colquitt County

Feeding Our Children a Healthy Dose of Language Nutrition

Nearly 40 percent of children in Colquitt County are living in poverty. That matters because 61 percent of children from low-income backgrounds have no books at home and hear as many as 30 million fewer words than their more affluent peers by the time they begin school. In 2014, only 33 percent of third-grade students in the county exceeded state standards on the CRCT promotional test in Reading—well below the state average of 46 percent.

Colquitt County Family Connection Collaborative on Children and Families is spearheading an effort to improve these results by collaborating with Talk With Me Baby, a powerful cross-sector coalition that is bridging the word gap by ensuring that every newborn in Georgia receives essential Language Nutrition: abundant, language-rich adult-child interactions, which are as critical for brain development as healthy food is for physical growth.

“We decided that early childhood is where we needed to focus to make the most difference,” said Janet Sheldon, Colquitt County Family Connection Collaborative executive director. “Children come to school not ready to learn—but we can turn things around in our county, starting now.”

The partners—Georgia Department of Public Health (DPH), Bright from the Start: Department of Early Care and Learning (DECAL), DECAL’s Early Education Empowerment Zone (E3Z), Georgia Commission on Women, and Colquitt Regional Medical Center—rallied around the importance of Language Nutrition. Because just as children require warmth, food, and protection, they also require Language Nutrition if they are to reach their developmental potential.

“Everyone recognized that simple engagement with the child is so crucial,” said Sheldon. “To do otherwise is neglect and has serious side effects.”

Spreading the Word

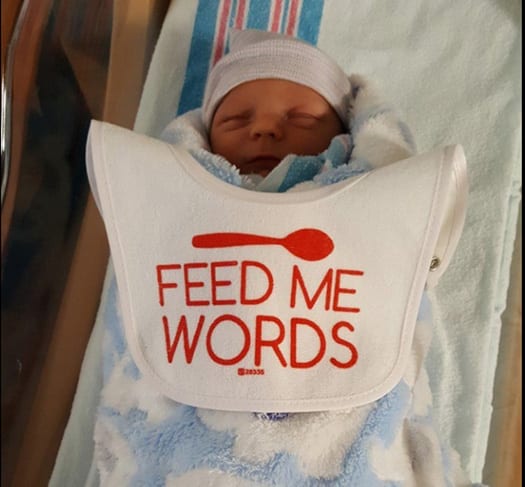

It is projected that 700 babies will be born at Colquitt Regional Medical Center in 2017, and every one of their mothers will go home with a Talk With Me Baby DVD produced by DPH. To kick off the initiative, DPH also provided bibs with the slogan “Feed Me Words” and a board book with the same message.

This program was made possible through a $10,000 grant for family engagement of young children from DECAL, as well as the guidance of Jill O’Meara, DECAL’s Early Education Empowerment Zone coordinator, whom Sheldon called her “go-to person.”

“The Raising of America: Early Childhood and the Future of Our Nation,” a documentary series about early childhood development, served as the centerpiece for the grant, which was aptly titled, “Something to Talk About.”

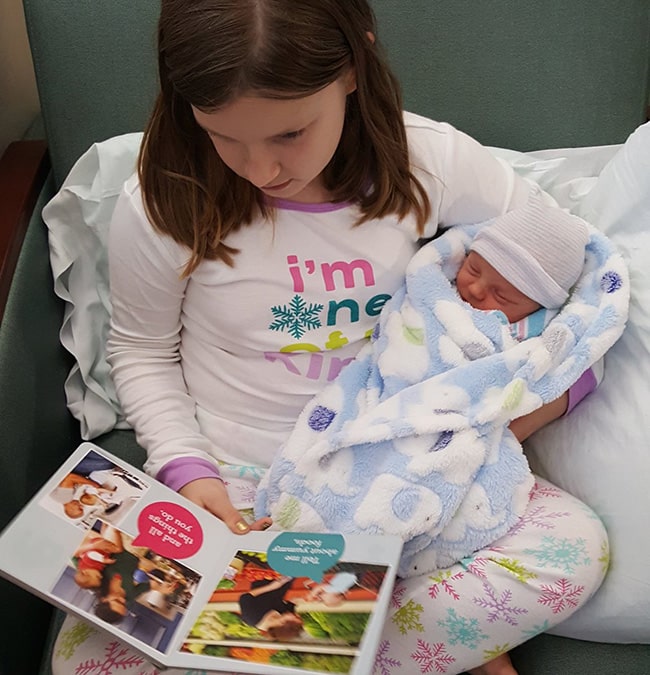

“The goal is for the word to spread that a baby needs direct eye contact and constant interaction by talking, reading, playing games, holding, and loving them,” explained Sheldon. “This is the most active time of brain development in a human and, without stimulation, will not develop to the full potential.”

DPH is also providing free training for the OB-GYN nurses and other professionals at Colquitt Regional Medical Center who interact with mothers and babies so that they can, in turn, coach the new parents about the importance of talking to their baby right away.

The Collaborative is planning to expand the program to make sure messaging about Language Nutrition is present throughout the whole process—at the OB/GYN office throughout the pregnancy, when the baby is born at the hospital, and at the pediatrician’s office as the child grows.

Erica Paez, M.D., a pediatrician at Colquitt Regional Pediatrics in Moultrie, is eager to incorporate the Talk With Me Baby video and supplementary materials into the resources she already provides for her patients.

“I always tell parents that smiling is one of the first ways babies can communicate, and then they start making sounds and words and phrases,” said Paez. “If you read to them, you help them communicate faster. The more time you spend with them, the more confident they will be. If you make this connection, it will be easier for them when they go to school.”

Paez noted that thanks to the Migrant Education Program (MEP), many parents in the county are already aware of the importance of talking and reading to their babies. However, she also sees patients with complex family situations and parents who may lack the tools and time to make Language Nutrition part of their daily routine.

“Some parents think the schools are going to do everything for the kids—but in reality, the family is such an important part of a child’s education,” said Paez, who sends each patient home with a book during wellness visits. “Routine and consistency has to come from home, and then complement that with the school education.”

Paez said many of the county’s bilingual parents she meets are inclined to communicate with their children only in English, because that’s considered the primary language in the United States. She encourages them to teach their kids to speak, read, and hopefully write in both languages.

“I tell them English is important—but your culture, your roots, your language are also important,” she said. “Being bilingual is good for their children’s future in so many ways—not just in terms of jobs and money, but also in terms of opportunities to travel and interact with other people.”

Breaking through the Poverty Barrier

According to Paez, starting these conversations about every aspect of Language Nutrition during prenatal visits is vital because it familiarizes parents with the concept and gets them thinking about talking and reading to their babies before they’re born.

“Children who read well are going to be able to comprehend complex situations, solve problems easily, and have easier social-emotional interactions,” said Paez. “If you invest in childhood, you are going to see a healthy society—but if you don’t invest now, you are going to see more problems in the future.”

Sheldon is already busy making more plans to invest in the county’s youth—from trying to get every child a book each month for their first five years; to getting parents signed up for programs like Ready4K GA and Vroom that help prepare children for success; to working with schools, child-care centers, and civic groups to reach more families in the community.

“We just simply want to get everyone talking,” said Sheldon. “I liken it to how cigarette smoking used to be perceived—and now we all recognize the health problems for the smoker and the ills of secondhand smoke. Each year, we need to keep reaching the families that have had babies. How can anyone make a change if they don’t know the facts and the unparalleled position they hold for the future of their child? It is such a vital message to get out—and poverty need not be a barrier.”